Writing a new constitution is one of the most important and difficult things a people can do, but if you want to turn up the level of difficulty from high to insanely high, try crowdsourcing it with 9 million of your neighbors. In 2017 the megalopolis of Mexico City adopted a new constitution, taking the momentous step to convert from a federal district to a city-state. While a document such as this is often drafted by political insiders behind closed doors, Mexico City sought wide public input.

Gathering ideas and suggestions from a population of 9 million demands careful planning and creative thinking in equal measure, so the City asked its creative team Laboratorio para la Ciudad (Laboratory for the City) to lead the crowdsourcing effort. The result was impressive: some 300 proposals and almost half a million signatures in support. From this, 76% of the ideas were incorporated into the final document, which became law in September of 2018. With this remarkable success barely behind them, the Laboratorio ceased to exist just a year later. Poof! Gone. What happened?

The Laboratorio had a short existence. Miguel Ángel Mancera, Mayor of Mexico City, appointed Gabriella Gómez-Mont Chief Creative Officer in 2013 and she founded Laboratorio shortly thereafter with the goal of bringing new problem-solving approaches and a wealth of creativity to government. Most of the Laboratorio’s work was bottom-up, meaning the lab’s 20-person team were collaborating with citizens, entrepreneurs, and other “unusual suspects” in addition to the expected work with fellow government officials. The Lab used its sidewalk credibility to do things that had previously been beyond the ability of government, like creating a map of the informal network of micro-buses that crisscross the city. In another project, Laboratio’s strengths in mapping and participatory processes helped the government of Mexico City bring new levels of attention to the city’s 3 million youth. They developed tools to map children block by block and then correlate that with green spaces and other public services, resulting in indices of segregation and marginalization that revealed “hotspots.” This allowed the government to be more targeted in their efforts to address spatial justice in a city that struggles with inequality.

Five years went by in a flash, and then a different government took over from Mayor Mancera with new priorities and the Laboratorio was closed. In Gómez-Mont’s telling, the Laboratorio’s closure was “not a disappearance, but the afterlife.” Gómez-Mont is sanguine despite what might be perceived as a setback. She asks rhetorically, “Even though there is an institutional carcass on our hands, is there an idea that has persisted?” Indeed, many of the Lab’s alumni are now applying their perspective and skills in other settings, continuing the mission of the Lab beyond the formal container of the organization.

In that sense the “afterlife” of the Lab may someday prove to be more important than its five year lifespan, with those 20 alumni sparking changes in yet more contexts both in Mexico City and beyond. Still, it’s hard not to wish that the Lab had been maintained in its productive and inspiring form. How would Mexico City be different today if the Lab were continuing to do good work, employing a team, and producing a stream of alumni? How much larger would the ripples of change be? We cannot know the answer to these questions, but we can and should use this story to ask how future efforts that share some resonance with the Lab can be made more enduring.

This story is about government, but the implications are more broad. It is relevant to anyone who is interested in meeting the needs of society with creativity and care through design for social innovation (DSI). Are those designers working in social innovation forever condemned to see labs, centers, pilot projects, and other vessels of their work, come and go on short-term cycles? This is not a question but a call to action.

If you believe that government is important, that business cannot continue to function in pursuit of predominantly financial goals, that the wicked challenges of society require new ways of doing things—then the story of the Laboratorio invites us to examine the sustainability of design for social innovation practices. What would increase the likelihood that the next Laboratorio exists for 10 years, and the one after that for 20?

Though the accomplishments of Laboratorio para la Ciudad were singular, the story is, unfortunately, not unique. Working outside the boundaries of traditional ways of doing things weds exhilarating freedom to existential fragility. The Lab is just one of many examples showing how difficult it is to change the way governments, businesses, and non-profit organizations meet the needs of contemporary humans and make them more effective against the demands of the day. With countless pilot projects, startups, and labs that have come and gone, the question is how the sustainability of design for social innovation practices can be enhanced. If that’s a question you care about, this book is for you.

To understand the sustainability of DSI around the world, we conducted a global survey that resulted in 45 succinct case studies. Each one presents a project, describing both the outcomes and the setup that allowed the work to be possible. This survey was created via a bottom-up process that also surfaced a slate of thematic issues related to the future of design for social innovation, each of which you will find addressed in a roundtable discussion. The organizing principle behind our book, and the two years of effort that went into it, is a hunch that design for social innovation as a field of practice is at a unique moment of maturation. It’s time to move beyond the attempts to explain or justify the role of design within social innovation processes and instead put more emphasis on how the field is growing and evolving. It is time to focus on identifying the approaches that enhance the sustainability of this practice.

We use the word “sustainability” in its most basic sense: the ability of design for social innovation work to continue. Our hypothesis is that sustainability is the result of perceived legitimacy, which grows when the outcomes of design work are perceived to be positive, which itself requires that the work and its goals be legible.

We explore this hypothesis through case studies, data analysis, and roundtable discussions. The cases are structured in a manner that will make projects legible on a very basic level, describing who was involved, how it was supported, and what happened. We have also asked each of the case study teams to describe their own approach to measuring impact. With only 45 case studies, this book provides more data points than it does conclusions, but our hope is that presenting the cases in this format allows the reader to get to know the work in a deeper way with regard to both impact and questions of business and organizational models. Too often these dimensions are left out of case studies in this field.

While we acknowledge that different political, economic, social, and cultural contexts make it difficult to create a depth of comparison between projects in different regions, we also recognize that practitioners of design for social innovation can still feel isolated. As the DSI field is maturing, we must strengthen the many communities of practice that are forming within it, and knowledge sharing among designers is key. The ability to compare and contrast one’s experiences with that of others to identify reference points and find patterns of similarity and difference fuels the collective confidence and potential of DSI overall as a field. The sustainability of a field comes easier when those in the thick of it feel that they have a cohort of peers who they can learn from, collaborate with, and even compete against.

As you will see when reading the cases, the distinction between designer and non-designer (and in some cases also the line between service provider and commissioner, client, or partner) is waning in relevance as the nature of this type of design work becomes increasingly collaborative and participatory. Regardless of how one identifies professionally, our goal has been to help readers contextualize their understanding of social innovation within a global context. It used to be the case that a philanthropic foundation or government who hired designers was a rare occurrence indeed. Fortunately, the world has changed and that is no longer the case, as can be seen simply by scanning the impressive list of organizations that are highlighted as “clients” (in the broadest sense) in these cases. Nevertheless, because the design process asks those who commission it to be comfortable outside the common logic of linear, quantitatively inclined ways of working and top-down strategic planning and decision-making processes, it puts individuals commissioning design work at risk of being perceived by their peers as acting in a manner that is risky and untested. To counter this, it is important to aggregate a wide variety of examples showing how design has been applied to very complex challenges with grace—and concrete results. Sustainability involves organizations happily commissioning future design or social innovation work and hiring their own designers; this book includes examples of both.

There is also a historical impetus for our interest in focusing on a selection of case study projects. In 2016, the editors of this volume penned LEAP Dialogues, a book that captured a polyphony of more than 80 individuals, mostly working in the United States, describing how they were able to build a career in design for social innovation. The focus of LEAP Dialogues was often intensely personal, even including “day in the life” essays that illuminated the professional rhythms of a handful of practitioners. What we found during that project is that design for social innovation had many small footholds across a wide variety of organizations as disparate as Nike, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the federal government of the United States, but that these examples sometimes felt tenuous in ways similar to the story of the Laboratorio.

The LEAP dialoguers each fought in their own way to convince managers, clients, partners, and peers that design had a meaningful role to play in philanthropy, business, government, and civil society. Personal fortitude features prominently throughout that book. Many if not all of the individuals whose stories are highlighted came to design for social innovation with formal training in some other subject, such as the traditional design fields, because, by and large, they started their careers before design for social innovation was formalized into programs of study. By the time the LEAP Dialogues book was released, however, the world was different and there were already a variety of places to study design for social innovation or related perspectives, as well as deeper and diversifying research on the subject.

As authors, we are also design and architecture educators, and we are encouraged by the evolution of design education curricula and educational offerings. With descriptions such as service design, strategic design, social design, transdisciplinary design, and transition design, some of the most effective programs today manage to avoid the trap of design “solutionism” that has become synonymous with human-centered design. In place of easy answers, “critical pedagogies” enable students to become reflective practitioners and principled citizens. The best programs keep idealism and a sense of purpose intact while teaching against the reductive seduction that “doing good for others” can so easily invite. We cannot quite claim that the current generation of graduates is leaving our schools with a fully embodied comprehension of the grit, patience, and humility DSI demands—such learning comes from the doing. That said, these are individuals who are entering the field with a healthy dose of criticality, self-awareness, and much more than an inkling of the systemic complexity they will be encountering head-on.

We see in our students a widespread desire to engage in socially meaningful work, though not all are fortunate enough to find a supportive place to practice in this way immediately upon graduation. Anecdotally, it would seem that there’s a deeper well of design talent interested in social innovation than there are organizations yet seeking that talent. Likewise, among design practitioners we see a broad interest in mission-driven work and applying design methods and mindsets at a strategic and systems level of intervention. Alas, connecting that intention to real projects still takes some doing. Acknowledging this reality of design for social innovation today, we set out to assess the ongoing maturation of the field so that, in part, we could confidently tell our students that the future they see for themselves is a legitimate and growing option.

It’s not just our students who are asking questions about the effectiveness of their tools and methods, and contending with the limitations of the mainstays of design education today, such as human-centered design and participatory practices. Practitioners and students alike are aware that many of our popular design and social change narratives remain riddled with problematic asymmetries of power, class, race, gender, and geography. As we watch the centers of gravity of our globalized world diversify and become displaced, the shortcomings of the 20th-century industrial era’s design canon, dominated by the Global North, are coming into full view. The good news is that we can point to encouraging signposts that a more inclusive approach to DSI is emerging.

Focusing on projects that have been implemented in some manner usefully directs our attention toward examples where the teams doing the work have sought validation of their hypotheses, which is another area where design for social innovation is showing new maturity. Examples like Kuja Kuja (p320) and the Financial Literacy for Ecuadorian Microentrepreneurs project (p170) demonstrate how designers are integrating quantified validation in their work, alongside qualitative self-reflection that has been pervasive in design practice for some time. Validating the outcomes of one’s project demands that the project actually transitions off the whiteboard, which in turn brings the details of implementation more clearly into the core of the project. As a colleague put it rather more poetically, “innovations will wither on the vine without a clear path to implementation.” We’re seeing less patience for blue sky thinking and more of an appetite to get design practice out under actual blue skies, tested by the real world but also having a clear impact in the real world.

As demonstrated by the projects we highlight, designers appear to be much less naive about walking into contested spaces claiming some kind of neutrality. Through highly transdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the Civil Society Innovation Hubs (p364), we see that building trust between all of the actors involved in design for social innovation is not a side effect of the work but a primary enabler. Social innovation is the work of answering society’s old questions in new ways, and it is seemingly impossible to do so in a transactional mode. This makes the traditional mystery that surrounds design practice and methods untenable. None of the projects in this book involve magical efforts by designers which are then revealed to astonished clients, like a sparkling new kitchen unveiled at the end of a home makeover television show. Instead, projects like Equity by Design Immersive Series (p74) and the Edmonton Shift Lab Collective 1.0 (p66) show us that design for social innovation is increasingly being used to break open the precious “sealed box” process previously used to exclude many from the acts of design and the decision making that happens therein. Where genius exists in this book, it is not personified by lone creatives, but embodied by trusting collectives.

Executing projects that directly touch the lives of some of the most marginalized members of society amplifies the stakes of design for social innovation, and the partners that fund and commission this work are right to be careful about adopting new practices. The cases in this book demonstrate the extent to which the buy-in of funders and partners makes or breaks a project. The cycles of reciprocal learning with design teams become heightened when projects recur or grow over long durations, as in Paddy to Plate (p262), Solo Kota Kita (p358), and The Human Account (p120). Unquestionably, this deeper alignment between DSI practitioners and their partners across sectors should be a source of optimism. The manifestation of projects that are operating at mounting scales of intervention and involving multiple actors is an indicator of the growing adoption of design by players across the spectrum of social innovation.

That’s the positive story, but design for social innovation is still finding its footing in numerous ways. All too many DSI projects remain high-cost experiments and bespoke solutions that struggle to move beyond the pilot stage of implementation. When this reality is acknowledged by the team, as in the case of Nest co-study spaces in Tel Aviv (p220), it can be a productive learning outcome, but when this tendency is swept under the rug it perpetuates the image of design as an ineffectual and resource-intensive way of working.

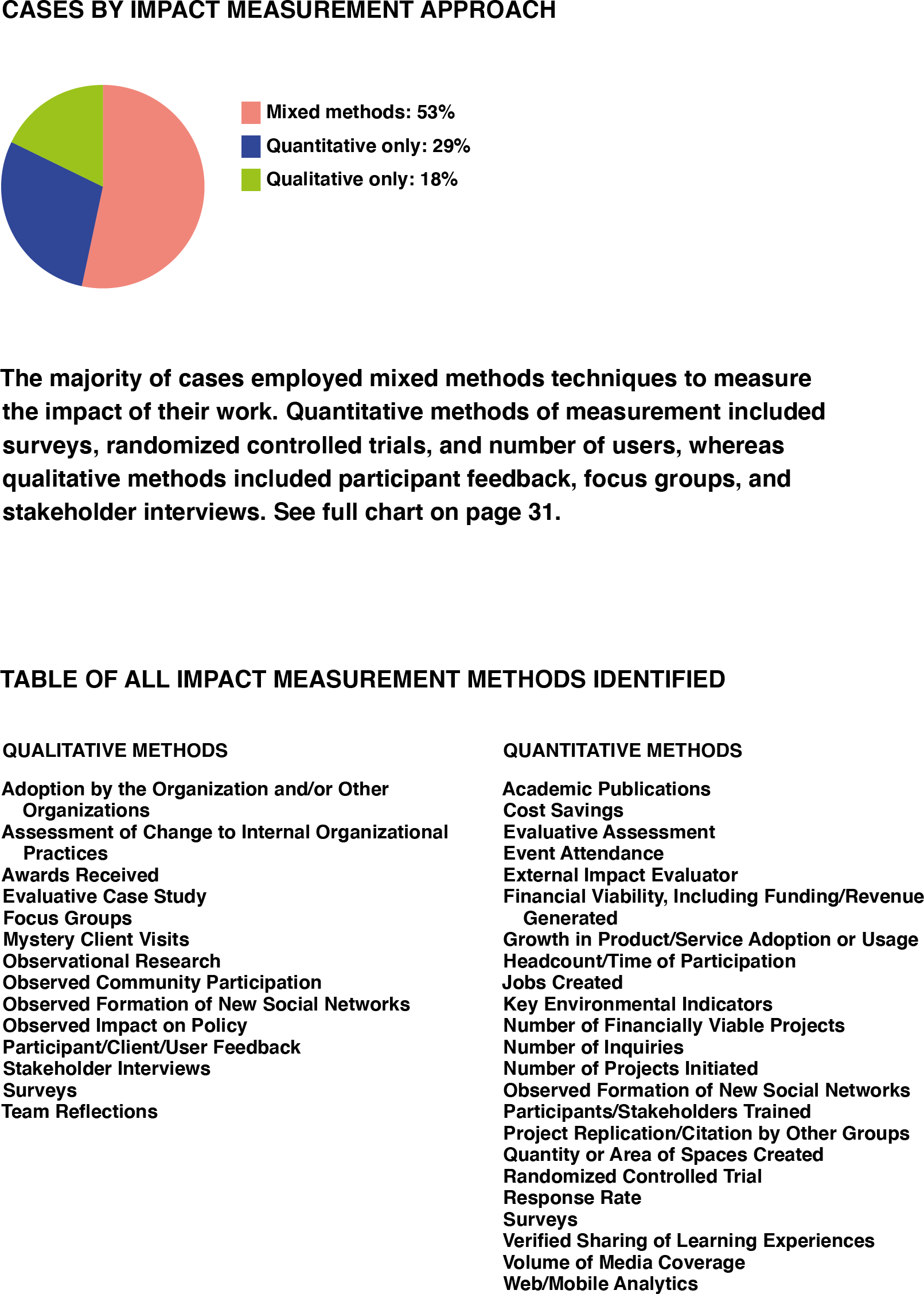

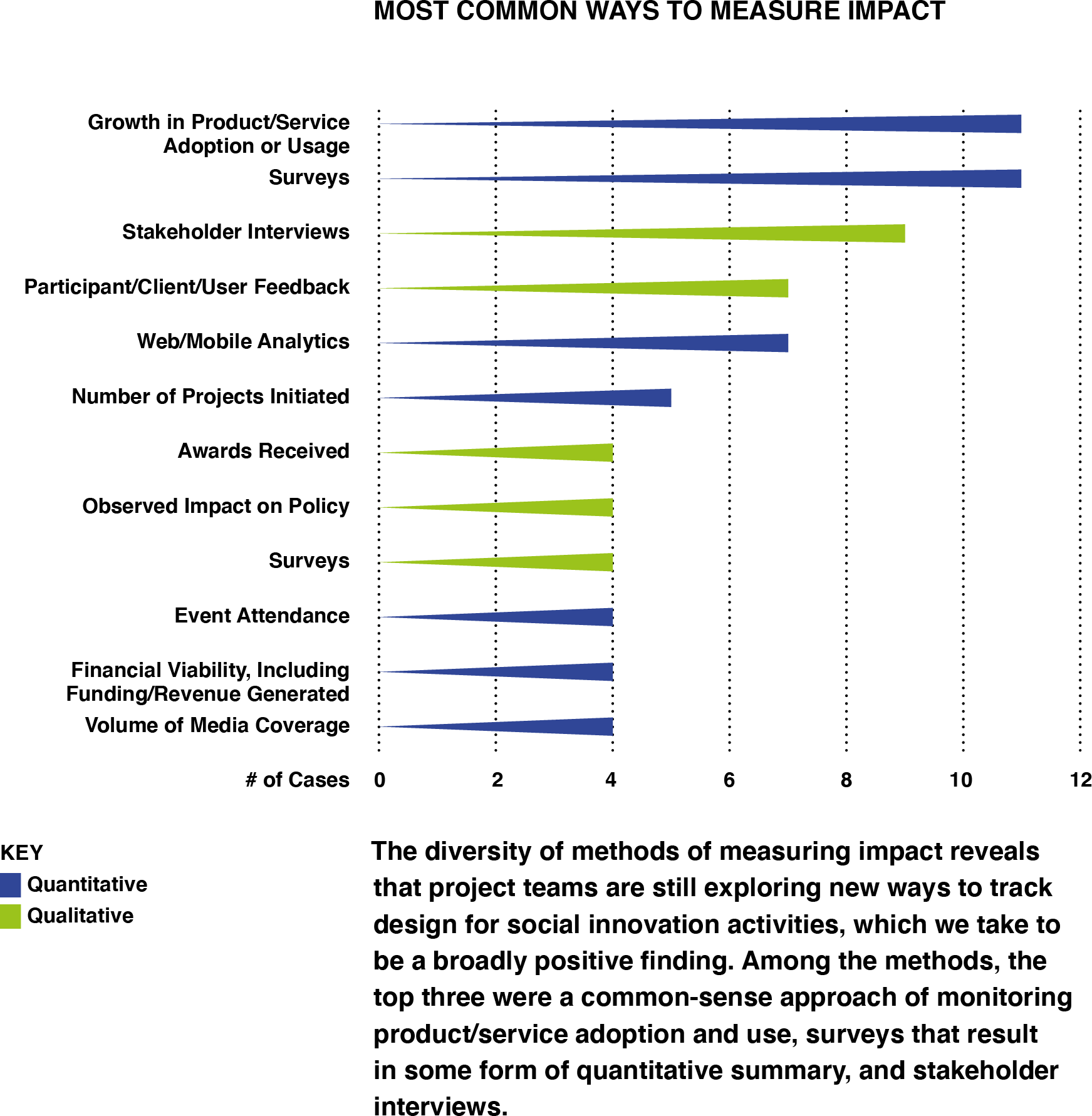

While the cases in this book employ 37 different methods of measuring the impact of design for social innovation work, truly identifying and understanding the unique contributions of the design process and the role of the designers involved remains a less than obvious task. This difficulty partially stems from the highly collaborative nature of work, but the ambiguity here is further amplified by the gap between the technocratic and often mechanistic orientation of the structures in place which are opposite of the free-form and generative organizational environments that typically nurture creative processes and enable innovation to flourish. Is it reasonable to use the logics of yesterday to assess outcomes that represent elements of tomorrow?

Every One Every Day (p180) provides a useful example through which to consider this rhetorical question. The project presents a possibility of community activation that is outside or parallel to the status quo of economic and governance structures of the UK. It asks us to ponder what success and growth look like in such a project. Does growth equate with more money, more jobs, and a bigger footprint, per many of our accepted norms? Or is it possible through a project such as this to see new ways of understanding growth and progress, not on the terms of industrial society but as determined by members of a community themselves.

The contradictions lingering in this brief assessment of the current state of design for social innovation are why we felt compelled to mark this moment in time with a survey of practices around the world. We set out to understand it from two angles: by gathering a broad set of representative, concrete examples in the form of cases; and by inviting a diverse mix of thinkers to join roundtable discussion reflecting on themes emergent from the case study research.

With DSI efforts being multi-stakeholder, intensely collaborative, and social in nature, one of the challenges of writing about it is that parsing exactly what was done and how it was accomplished can be difficult. In an attempt to keep the research grounded, we focused the case studies on projects rather than organizations or teams. Projects as the unit of analysis offer a ripe nexus between teams of “doers” and their clients or commissioning bodies, as well as between intentions and impact. This allowed us to get more specific about the details of who did the work, critical contextual factors that enabled the efforts, what was done, and the impacts. In recognition of the contours of each project, we’ve chosen to present the cases as narratives. We crafted these over several iterative and collaborative rounds of writing from survey data and the insights provided by the teams whose work is featured.

In addition to the written narrative, we collected metadata about each of the cases. Our intention in presenting the metadata is to get concrete about the details of the work in a format that is standardized across very disparate contexts. However imperfect this approach may be, it gives the reader the ability to compare and contrast the case studies more directly so that points of difference and convergence become easier to spot. Indeed, visualizing the cases in a literal sense became a fascination for us as well. Each case is presented with a “flower” graph that is generated using the data we collected about the project, explained in more detail on page 38.

We sourced case studies through a bottom-up process that started with an open call via the web to submit projects that the submitter considered to be a recently completed (or ongoing) exemplar of design for social innovation, defined in whatever way they saw fit. This effort was bolstered by the contributions of an International Editorial Advisory Board with deep and diverse knowledge of the work happening in their regions and around the world. In addition to the requirement that the projects be implemented in some fashion, we sought case studies that were lesser known to the international community. The result was nearly 200 submissions.

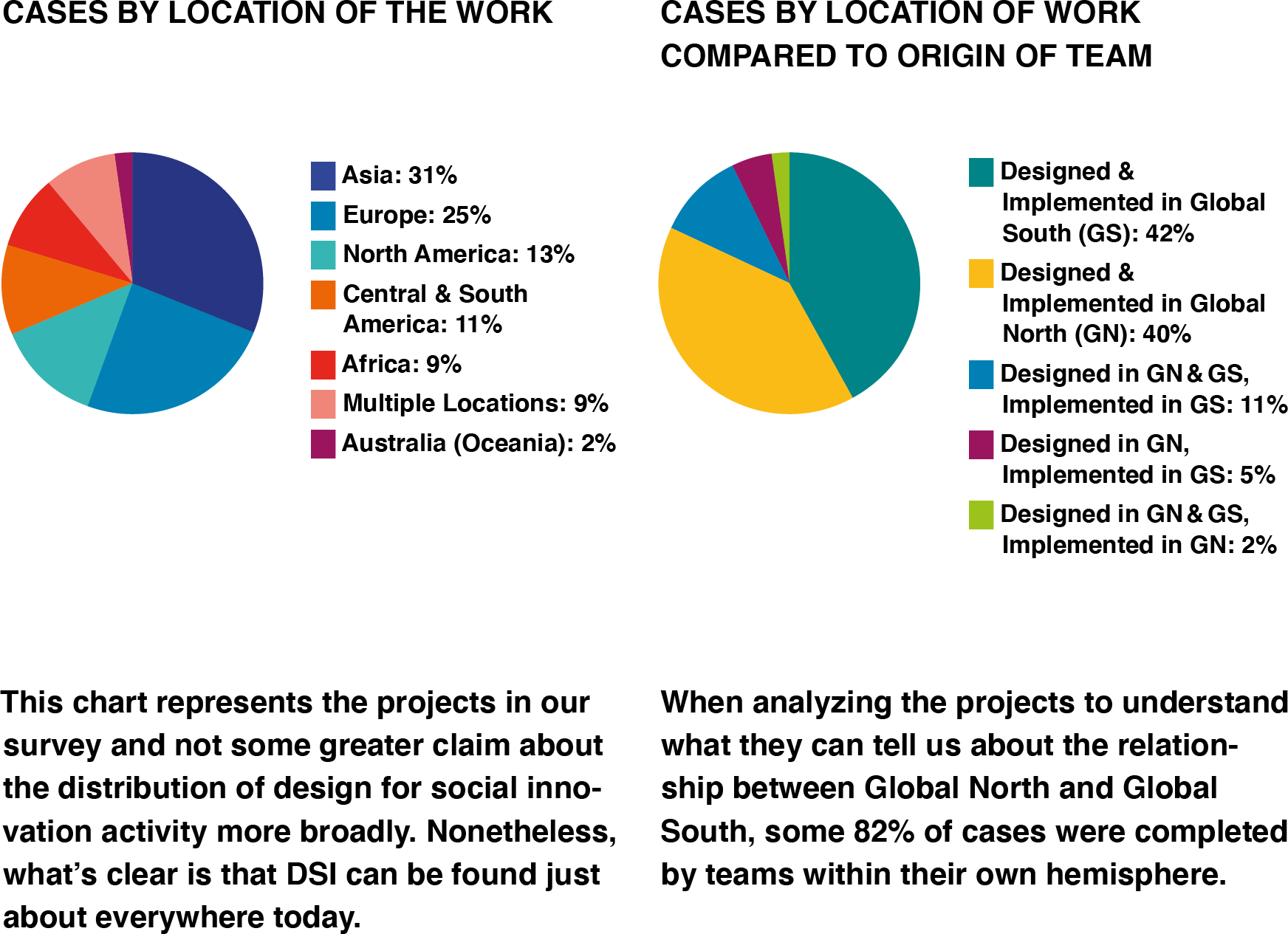

We spent long hours winnowing this large pool down to a set of 45, while using the projects as lenses onto the world—what do they tell us about design for social innovation practice right now? Where are the hotspots of interest, excitement, or struggle? What causes the threads of similarity that we see streaking through these projects? Seemingly simple questions such as the location of the designers compared to the location of the client or partner organization became entry points into more complicated issues. Understanding the geography of a project in more discrete terms leads quickly to questions of power. From where and to where does the money flow? Who’s making decisions and how well do they understand the context? Knowing more about who was involved and the type of their organization allows us to begin to understand modes of partnership and collaboration. Getting precise about what was created during a project represented an invitation to confront the strengths and also the edges of DSI practices.

In other words, the intention has been to capture projects through these case studies that, while singular and specific endeavors, allow us to start gaining a more integrative view of DSI practice overall, especially when viewing these projects as a set. The metadata analysis and the complementary insights that emerge in the roundtable discussions engage with the tension between projects and practice, between parts and wholes.

Once we made the final selection of case studies, it was energizing to zoom out and look for thematic veins that ran across them. A handful of themes emerged: power, international development, organizing models, partnerships, mediums of change, measuring impact, and growth. We chose to organize the book’s chapters with each of these themes and anchor them with roundtable discussions that brought together academics, practitioners, and case study contributors. Needless to say, while these seven themes are critical to the future of DSI, they are far from simple to capture, let alone resolve, by gathering just a few individual perspectives for a single discussion.

In the section that follows, we summarize the chapters of the book while presenting findings from our study of the quantitative data that emerged from the aggregate view of 45 case studies from around the world.

Power is ever-present in social settings, yet often hard to identify, and harder still to talk about, which is why it is a critical topic for the future of design for social innovation. Mariana Amatullo, Fatou Wurie of UNICEF, Ahmed Ansari of NYU, and Shana Agid of Parsons School of Design at The New School address power and its embodiment and distribution across varied geographies in this discussion. Interrelationships across space, people, institutions, and political economies is at the center of this roundtable.

How does power play out in problem-definition, problem-solving, and in the narrative of the project and solution? Who is given credit in a project and whose voices are lifted up? What shapes the directional flows of power, including education, perceived or promoted expertise, tools and resources? To date, many of these things have flowed from the Global North (and, more specifically, Western Europe and North America) into the Global South.

Anchored by three educators, this roundtable also delves into design education and its relationship with practice and community-based work, including themes of colonialism and the legacy of design’s formal emergence as a discipline in the industrial era. They question a pervasive myth in design education, challenging the notion that it is possible for the designer to ever be neutral. Design for social innovation, with participatory practices at its core, is inherently relational. Design education must not only shed the myth of neutrality but also must look to new texts, histories, and contexts as they seek to find an ethical and truly successful way forward. Designers, this discussion tells us, should also widen their understanding of what it means to “be a designer” and to become more inclusive of multidisciplinary and community expertise in that regard.

In addition to providing information about their projects, we asked case study respondents to tell us about the state of design for social innovation in their region. The majority of contributors responded that designers enter into social innovation through other fields or disciplines. As one respondent explained, “There are numerous routes into teams like ours in the UK. Whilst practical design skills are important, they are not a prerequisite for the strategic design and policy work we do in our team. We are more likely to recruit for potential and mindset rather than specific or accredited design skills.”

Design for social innovation has grown as a practice in international development with the adoption of design methods and designers in key agencies such as UNICEF Innovation; the Airbel Impact Lab at IRC (International Rescue Committee), and the Amplify Program at DFID (the former UK Department for International Development), to name a few. Due to its complexity, international development is perhaps one of the trickiest areas for designers to navigate as effective contributors, making it essential to address as we think about the future of DSI.

Isabella Gady and Jenny Liu speak with Ayah Younis of the Airbel Impact Lab at the IRC; Sarah Fathallah, who applies her design practice to projects in the social sector; and Robert Fabricant of Dalberg Design. Together, they explore the extent to which design is recognized and practiced in international development, and its relevance. They reflect on the interplay between established practices of traditional international development that are rooted in the social sector, including community organizing and participatory research. They also discuss human-centered design, agile practices, and tried-and-true techniques such as prototyping in the context of this work.

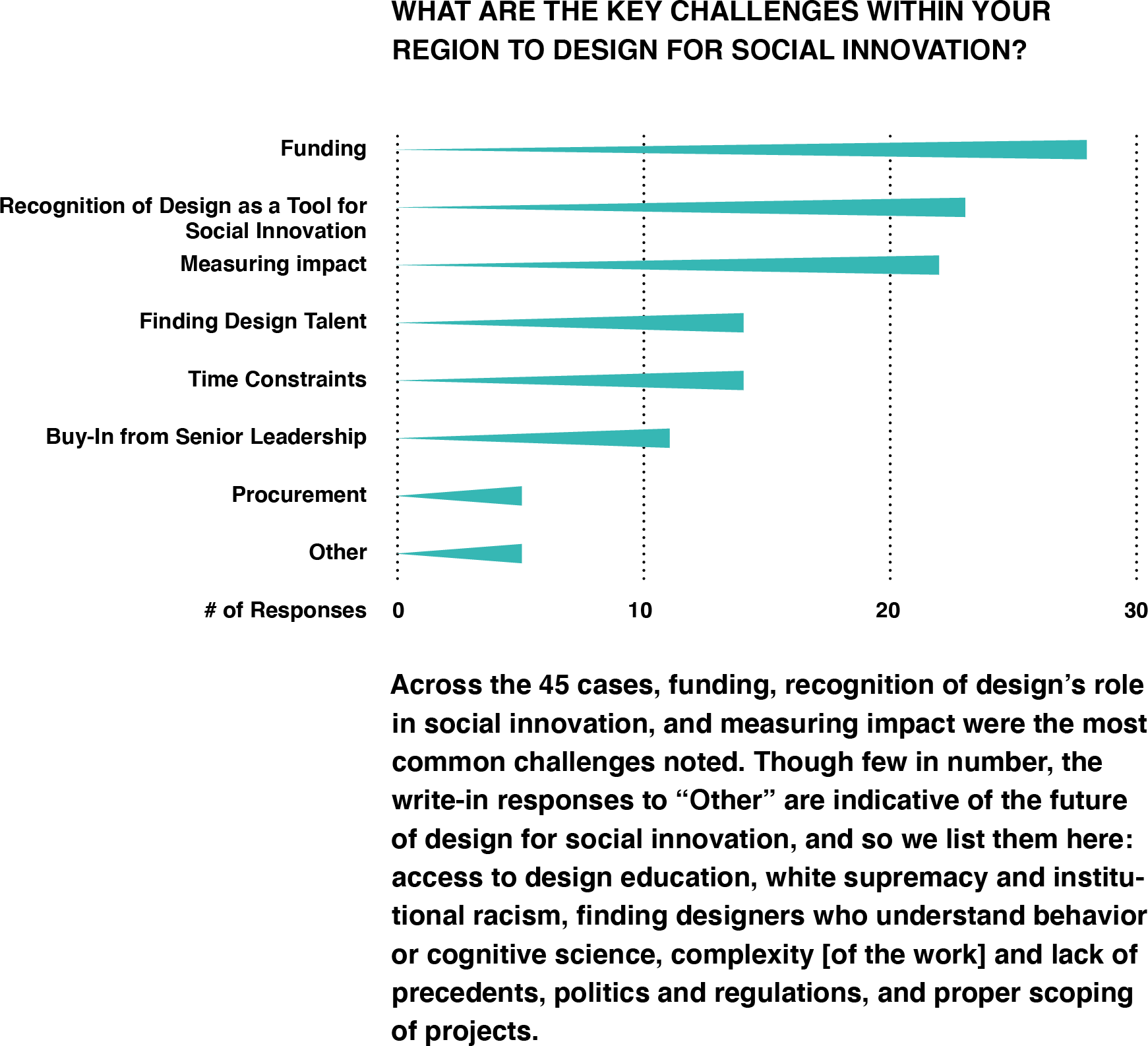

Central to this discussion are the limitations of traditional funding models in the international development space. Project-based funding models hinder the ability of designers to address root causes. This funding model often stymies long-term interventions that strive for more significant impact. While competition can spur improvement and development, the panel explores how competition between designers also detracts from creating a culture of shared knowledge and best practices. The discussion further touches on money flows within the social sector and international development, and a certain dependency upon—and complicated relationship with—philanthropy. The reality is that funding is what makes international development work possible. And yet the complex mosaic of financing sources (government allocations, international donor funds, and philanthropy) and the process of securing funding can be incredibly cumbersome and resource intensive. In the worst-case scenarios, these dynamics lead to a cycle of grant-chasing that further entrenches problematic power dynamics between funder, grantee, and community members.

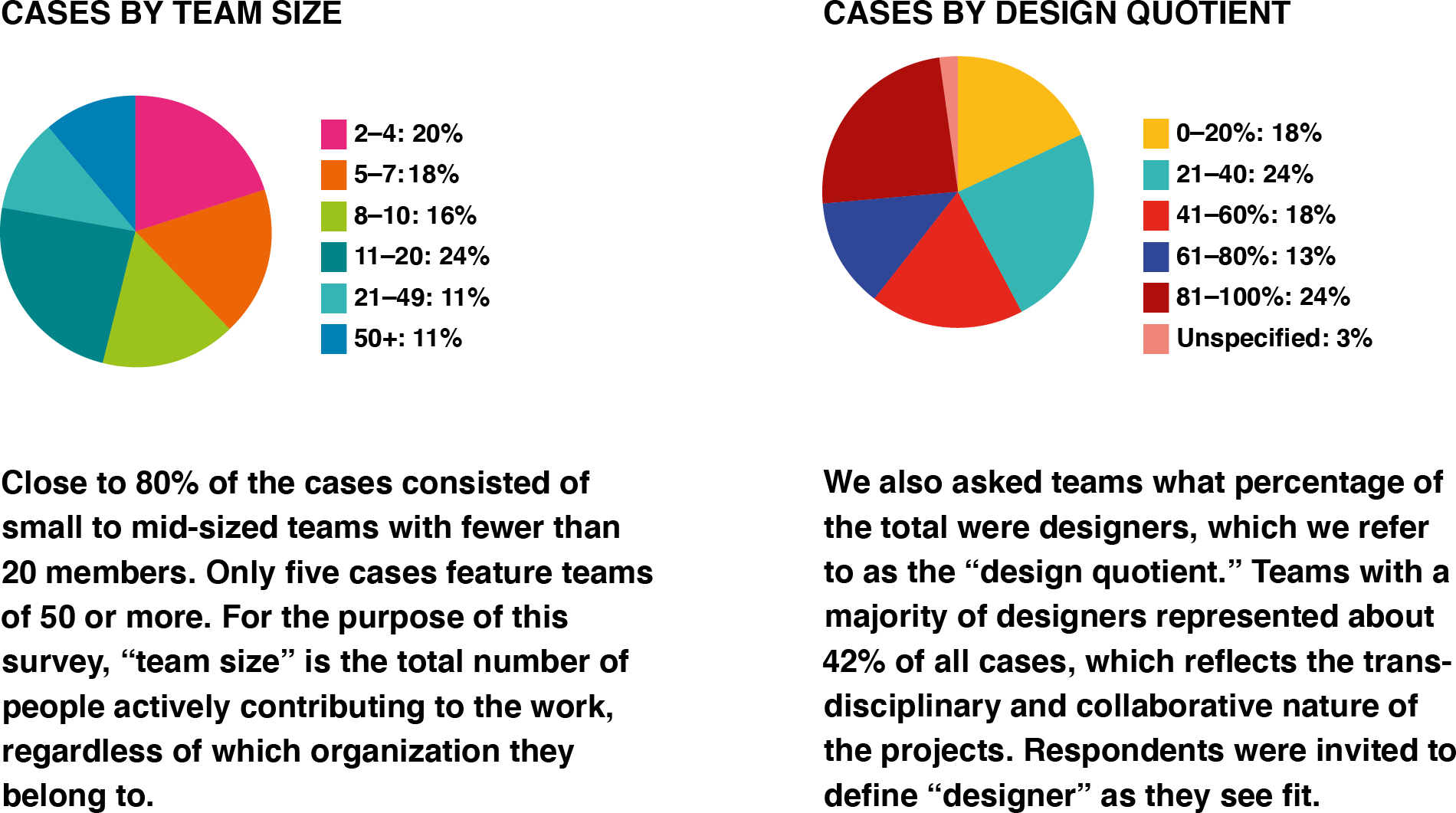

Design is a team sport, and as the field of design for social innovation matures, those teams are getting larger and taking on more diverse forms. In places with active and predictable regulation and taxation systems, the form of legal entity or organization one uses to do their work can have an impact on who they get to work with and how they collaborate. Non-profit, for-profit, government, non-governmental organizations, civil society collectives, and a thousand variations are all possible, but the work of design for social innovation often does not fit neatly within these structures.

Dependent as it is upon a broad spectrum of relationships, different kinds of resources, long and fluid timelines, and open-ended methodologies, the question of how to organize as a legal entity takes on more profound meaning in the context of social innovation design efforts, and so it became the subject of a roundtable discussion in search of loopholes and other promising avenues yet unexplored. Bryan Boyer (who splits time between a for-profit and academia), Alexandra Fiorillo of GRID Impact (a social enterprise), Christian Bason of Danish Design Centre (a mostly government-funded non-profit), and Tessy Britton of the Participatory City Foundation (a charitable organization) consider the day-to-day work of design for social innovation and the gaps between the transactional, top-down structures of industrial society and the more nimble, relational approaches favored by many in the design community and growing within industry and government.

The panel addresses their desire to build longer-term relationships with partner or client organizations, and the need across the board to continue working to improve the perceived value of design. One way to index perceived value is through the volume of work that is funded via fee for service and that which is funded by government, which together account for approximately 50% of the cases in this book.

Collaborations are integral design for social innovation, occurring as it does at the intersection of sectors, disciplines, and models. None of the 45 cases in this book—indeed, none of the 182 projects that were submitted to the initial call for case studies—feature designers working in a vacuum. Each case in this book describes some form of collaboration: formal or informal, with universities, corporations, governments, NGOs, non-profits, community organizations, advisory boards, committees, subject matter experts, and community members.

Jennifer May, Nandana Chakraborty, and Vivek Chondagar of Digital Impact Square, Jesper Christiansen of State of Change, and Fumiko Ichikawa of Re:public look at the ins-and-outs and ups-and-downs of partnering up. They examine the models, scale, and scope of the partnerships each participant is engaged in, as well as how they set clear expectations at the beginning of their collaborations. Like the ground beneath our feet, expectations inevitably shift, and what to do in those instances is a topic of lively discussion in this roundtable.

To understand partnerships on a more operational level, we asked case study respondents to tell us about the teams working on their projects. Were they small or large? Of the overall team, what was the “design quotient” or the percentage of members who identify as designers? Understanding the make-up of project teams more discretely helps the reader refine their understanding of where a “difference” is being made by designers (or not).

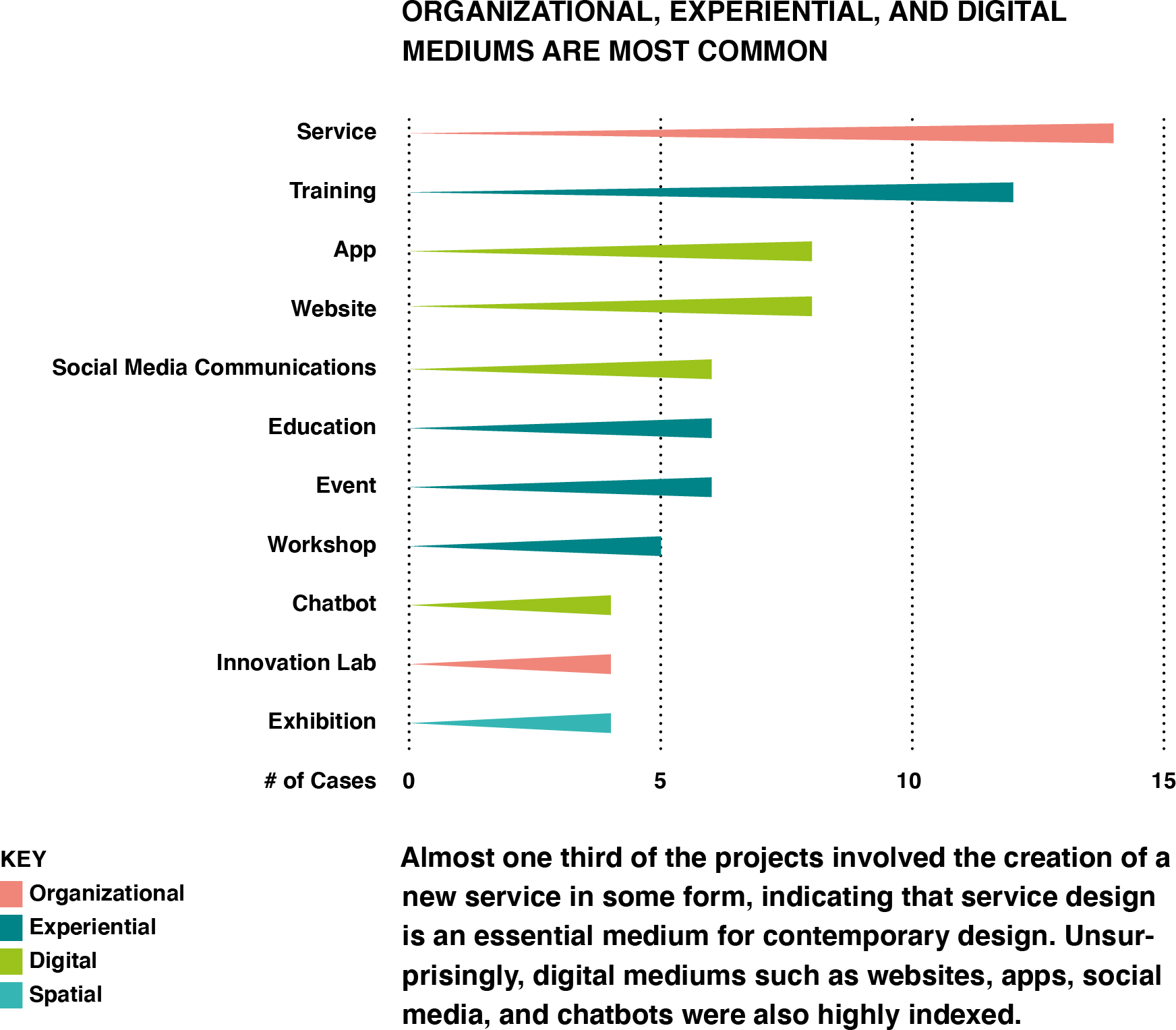

The purpose of design for social innovation is not to make things, but to facilitate social change, so designers must carefully and deliberately connect intention with outputs. Bryan Boyer, Debbie Aung Din of Proximity Designs, Jan Chipchase of Studio D Radiodurans, and Professor Ramia Mazé of University of Arts London dig into the many “mediums” through which design for social innovation is executed. They explore how to balance the creative and exploratory aspects of the design process with funder expectations to produce work that has a clear timeline, budget, and impact.

When the work of serious social innovation includes unconventional outputs, like a bottle of bespoke moonshine which you will read about in this roundtable, how do the project partners put a value on that output and ripple effects? The group sensitively teases apart the value of unexpected objects and experiences that invite stakeholders to participate in new ways, including opening their thinking to novel possibilities.

Ultimately, we learn, it requires defining and assessing the outcomes of a project beyond the outputs. Project deliverables may live on a shelf, but the most powerful examples of design for social innovation are able to make space for new knowledge, processes, methods, and questions in the hearts and memories of those who engage with it.

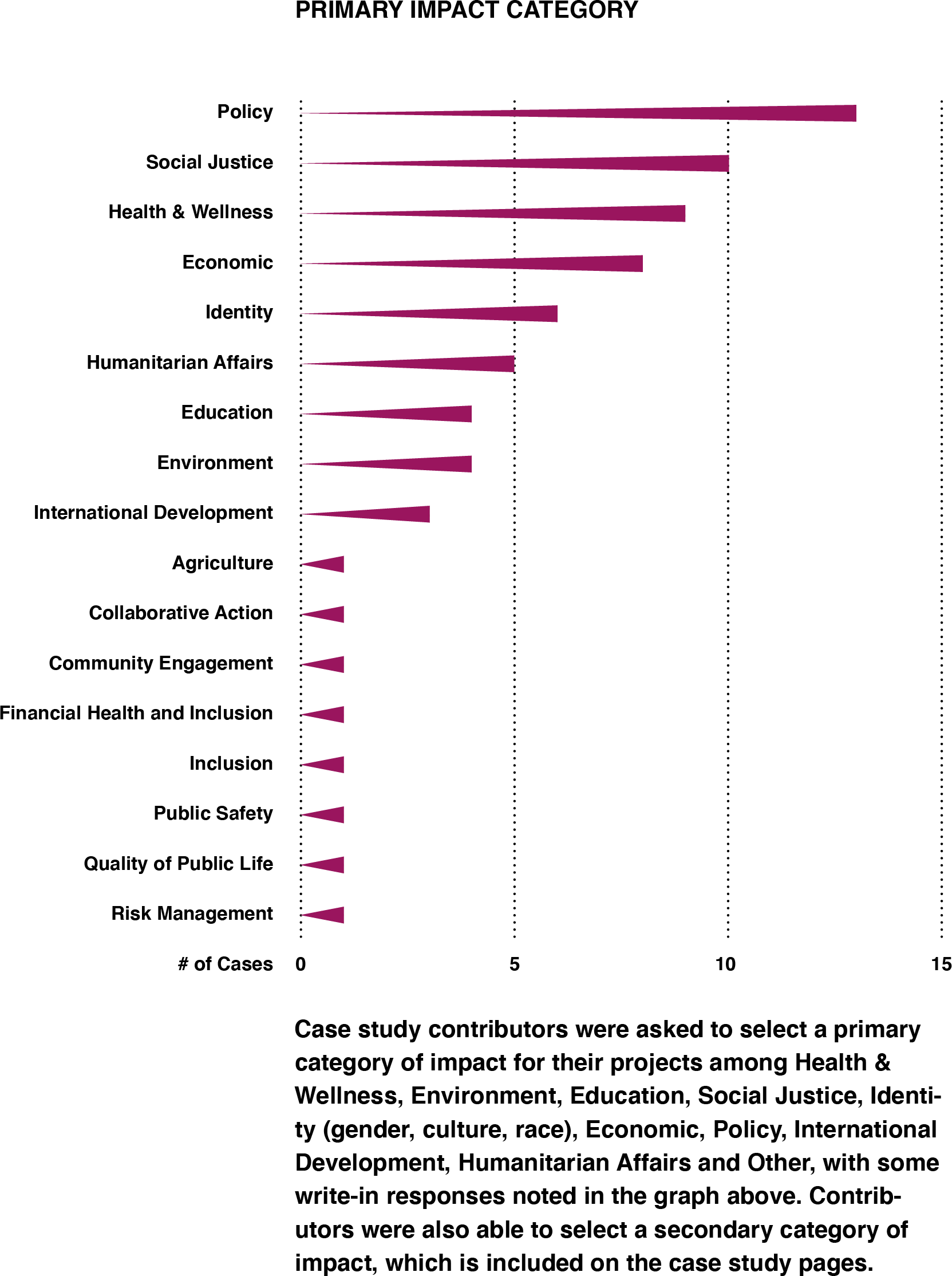

Design for social innovation does not matter unless it creates an impact in the world—and not just any impact but a positive and desired one. Mariana Amatullo, Stuart Candy of Carnegie Mellon’s School of Design, Chris Larkin of IDEO.org and Joyce Yee of the School of Design, Northumbria University, convened to discuss how designers assess whether their work is producing positive outcomes by design. Through their multifaceted conversation, the panelists surface three key barriers to measuring impact.

First, design for social innovation occurs at the intersections of sectors and disciplines and involves many stakeholders. Practitioners are often working through ambiguity, defining problem statements, research methods, and other project factors as they go. Taken together, this makes it difficult to identify clear theories of change and parameters for success.

Second, consultancy-based work is often mismatched to goals of design for social innovation initiatives. Developing and deploying methodologies for measuring impact takes time, especially for projects aimed at behavior change or social outcomes that take time to be adopted at scale. When design work is done under a consultancy model, the ideas are usually handed over to a partner to implement, subverting the possibility (and, some argue, imperative) to learn and adjust from the process of delivery.

Third, evaluation methods for design practices are immature, and the typical frameworks and methodologies used in international development, philanthropy, and social sciences do not always capture the intricacies of designed outcomes. Additionally, whether working across the globe or in one’s own neighborhood, power and cultural dynamics inevitably shape what success looks like, and for whom.

Finally, Andrew Shea, Indy Johar of Project 00 and Dark Matter Labs, Gabriella Gómez-Mont of Experimentalista (whose story also kicks off this introduction), and Panthea Lee of Reboot reflect on the field’s trajectory. They discuss the current plurality of ways to approach design for social innovation as well as how the field is evolving.

Central to this roundtable is the need to consider the ethical weight of working within broken systems and, when doing so, to redefine one’s relationships to such systems. This point highlights a goal shared by the panelists (and many

designers in this book), which is to promote greater participation in governance and self determination. While participation has been lauded as a way to increase responsiveness of government, that aspiration comes with subtle challenges. Is it fair to ask community members to take time away from their work, families, and lives to participate in fixing systems they didn’t “break” in the first place?

The panel interrogates whether design for social innovation could be anything but small-p political in nature; they address the importance for designers to be involved in the creation of new governance, knowledge, and design of organizational structures. They point to the role that designers are playing to facilitate conversations and collaboration around these topics, and why it’s important for them to embrace their agency during these processes.

Let us go out on a limb and imagine that you won’t be satisfied by knowing that compelling examples of design for social innovation can be found on six continents, with goals as diverse as improving community dynamics in apartment buildings, to supporting LGTBQ+ rights, to expanding access to clean drinking water. We suspect you will nod your head when reminded that college degrees are offered in (or largely focusing on) the subject, and show only slightly more interest in the fact that organizations including the United Nations, national and local governments, globally active foundations, and a long tail of many others are employing designers to help make progress on the thorniest issues. If these assumptions of ours have proven correct, it’s because the type of people who are drawn to design and social innovation alike are hungry for deeper and more lasting change. If you’ve been working in this area for any length of time, all of the facts stated above will likely be reassuring, but still not satisfying. Sure, design for social innovation has some legitimacy now… so what next?

The answer to that question is precisely why we felt this project was important. In focusing on articulating the impacts of design for social innovation efforts, we hope that this survey will contribute to the growing and necessary discussion about the forms of evidence that designers use to know when their efforts are successful or not. Though true that the qualitative, relative, and often indirect outcomes that designers value cannot be readily reduced to numerical metrics, we owe it to ourselves as practitioners to build scaffolding between ways of knowing and doing, between regions, and between disciplines. In short, more discussions of what’s working and what’s not.

Humanity has some thousands of years of cumulative experience tabulating activities in the neat columns of a financial ledger. If it’s hard to figure out how to measure the impact of social, emotional, non-human, or environmental impacts (just to name a few alternative priorities), this should not come as a surprise. Rather, it’s an opportunity for continued, careful innovation with as much creativity as is applied to the projects detailed here.

This survey also hopes to prompt a discussion of how we draw comparisons across work that is so necessarily situated in the ontological and epistemological contexts of individual communities and unique geographies. As important as it is to apply an intersectional analysis, we also seek ways to draw comparisons across vastly different groups without capitulating to universalist frameworks. Pairing case study metadata and free-form narratives is our attempt to balance these competing lenses.

Every book is an artifact of its time. As this one goes to press in 2021, we see the world slowly emerging from the throes of the global pandemic. It is too soon to imagine the post-Coronavirus world fully. Still, it is already clear COVID-19 has only emphasized existing weaknesses in the systems of everyday life. This global health catastrophe has illuminated how interconnected everything is: health, social, environmental, and economic impacts all spill into each other. The pandemic has precipitated a unique cultural and social moment—a time of reckoning around the world that is bound to have ripple effects for the future of the field of design for social innovation.

Though named for the year 2019, the impact of the novel coronavirus that recently reshaped the globe is sure to last far longer. Likewise, when considering this survey of global DSI practices, it is apparent that the field has matured in ways that seemed far-fetched even just a decade ago. With vaccinations now being distributed and the grip of the virus apparently loosening ever so slightly, the global public health situation and the state of design for social innovation share one thing in common: in both regards it feels as if we’ve only just reached the end of the beginning.